American Cancer Society Grant Fuels Colorectal, Breast and Cervical Cancer Research

Four dedicated researchers from Michigan State University have received grants totaling more than $3 million from the American Cancer Society, or ACS, to find new ways to prevent, detect, treat and help patients survive colorectal, breast and cervical cancer.

MSU Researchers Fight Cancer for You

More than 250 researchers with Henry Ford Health + Michigan State University Health Sciences receive funding from federal agencies as well as other sources that supports their research focused on better diagnosis and treatment for cancer patients. They bring together diverse expertise across disciplines and, often, one advancement contributes to another.

Henry Ford + MSU Researchers Collaborate to Shift Pancreatic Cancer Outlook From Bleak to Bright

Pancreatic cancer is one of the most aggressive and deadly forms of cancer. The five-year survival rate is just 13%. On average, patients survive for only nine months after diagnosis and roughly 66,000 people are diagnosed in the U.S. each year. Now, researchers from Henry Ford Health and MSU are coming together to share their knowledge and expertise with the aim of changing this somber prognosis.

National Medal of Science Awarded to Oncofertility Innovator, MSU Research Foundation Professor Teresa Woodruff

Teresa K. Woodruff joined an elite group of Americans who have received two national medals of honor when President Joe Biden announced the latest recipients of the National Medal of Science on Jan. 3.

Researchers Use Virtual Reality to Modernize Health Care Training

Michigan State University researchers have developed a virtual reality curriculum to prepare health care professionals and students for the complexities of caring for patients with tracheostomies and laryngectomies.

Henry Ford Health, MSU Announce 2024 Cancer Research Award Recipients

Henry Ford Health + Michigan State University Health Sciences has named the award recipients of the 2024 Cancer Seed Funding Program. Building on the success of the 2022 and 2023 cancer research pilot and integration award funding initiatives, this year the program awarded 14 new cancer research awards totaling $700,000.

Fighting Prostate Cancer, From Farm to Table, at MSU

With a nod to bringing local, fresh ingredients directly to our dinner plates, Michigan State University researchers will soon be applying their own farm-to-table approach to the fight against prostate cancer. From therapeutic ingredient production to research and testing — it’s all happening at MSU.

The special ingredient in this approach is promethium-149, or 149Pm. This isotope has promising qualities for targeted radiotherapy — a process that delivers radioactive isotopes directly to cancer cells to damage their DNA.

The special ingredient in this approach is promethium-149, or 149Pm. This isotope has promising qualities for targeted radiotherapy — a process that delivers radioactive isotopes directly to cancer cells to damage their DNA.

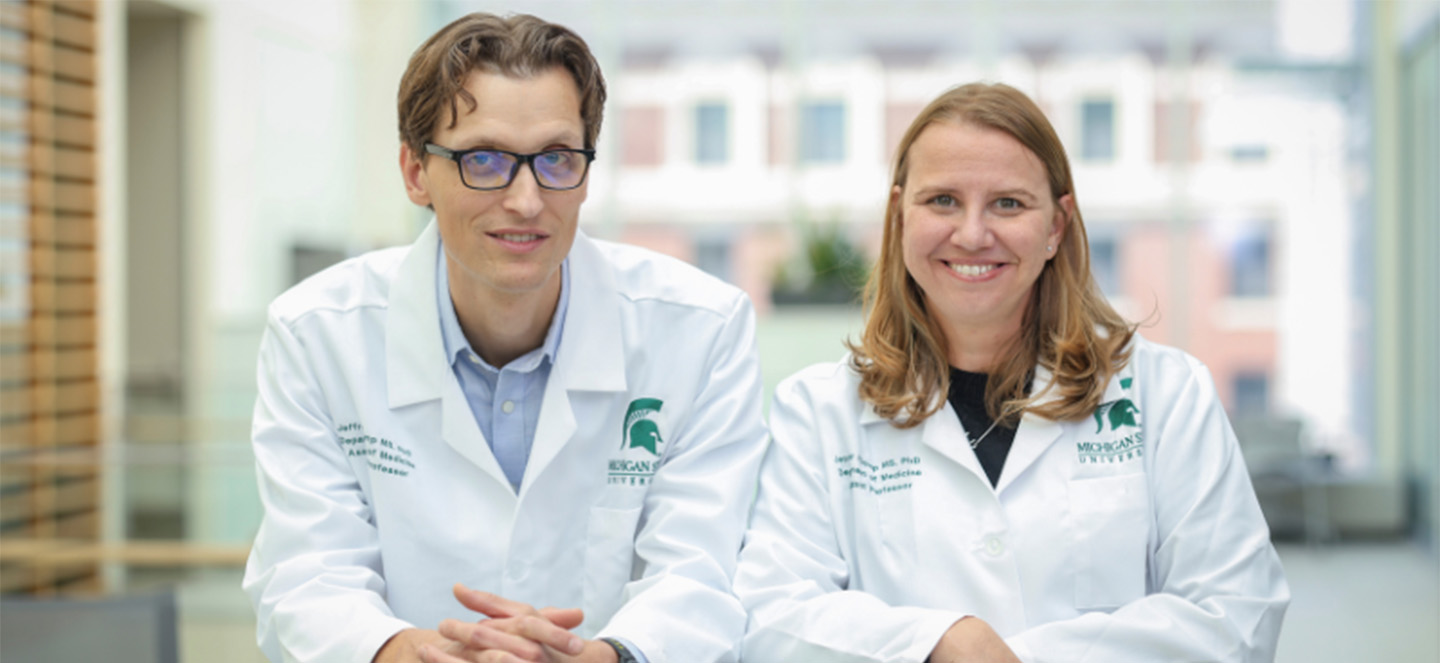

College of Human Medicine Recruits Leading Cancer Researchers Jeff and Jenny Klomp

On a sunny morning this past June, scientists around the world woke up to news that could fundamentally change the game in cancer research and care. And two of the people behind that breakthrough are now working at Michigan State University.

MSU Researcher Identifies Ways to Reduce Cancer Risk Among LGBTQIA+ People

Socioeconomic status, provider-patient relationships and rural living environments have been found to affect cancer screening behaviors for LBGTQIA+ individuals, according to a recent study from Callie Kluitenberg Harris, a doctoral candidate in the Michigan State University College of Nursing.

“With a better understanding of cancer screening discrepancies among sexual minorities, the probability of finding a cancer early is greatly enhanced and ultimately reduces the risk of death from a late-stage diagnosis,” Harris said.

“With a better understanding of cancer screening discrepancies among sexual minorities, the probability of finding a cancer early is greatly enhanced and ultimately reduces the risk of death from a late-stage diagnosis,” Harris said.

MSU, Corewell Health Mark 17-Year Partnership by Adding $1M Investment in Exploratory Research

For 17 years, the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine and Corewell Health in Grand Rapids, Michigan, have funded more than $27 million in exploratory and developmental research projects that have brought together the clinical and scientific strengths of both institutions.

Now that partnership, known as the Corewell Health – MSU Alliance Corporation, is adding another $1 million to the total with a new round of grant funding that will help advance innovative treatments for patients.

Now that partnership, known as the Corewell Health – MSU Alliance Corporation, is adding another $1 million to the total with a new round of grant funding that will help advance innovative treatments for patients.

Smarter Blood Tests From MSU Researchers Deliver Faster Diagnoses, Improved Outcomes

Medical professionals have long known that the earlier a disease is detected, the higher the chance for a better patient outcome. Now, a multidisciplinary team of Michigan State University researchers, in collaboration with experts from Karolinska Institute and the University of California, Berkeley, has pioneered a way to do just that.

A Catalyst for Change: Henry Ford Health, MSU Celebrate Groundbreaking of Research Center in Detroit

Researchers, community members, students, officials and more mark a pivotal moment as work begins on the 335,000-square-foot research facility. The Gilbert Family Foundation also celebrates the groundbreaking of the Nick Gilbert Neurofibromatosis Research Institute

It was a morning punctuated by celebration, collaboration and a visit from Michigan State University mascot, Sparty, as hundreds gathered to recognize the start of construction on the Henry Ford Health + Michigan State University Health Sciences Research Center in the New Center neighborhood.

It was a morning punctuated by celebration, collaboration and a visit from Michigan State University mascot, Sparty, as hundreds gathered to recognize the start of construction on the Henry Ford Health + Michigan State University Health Sciences Research Center in the New Center neighborhood.